If we project the later Anglo-Saxon Forests onto the coin find map, we see similar patterns.

Now archaeologists and modern geographers maintain that forests were extensively cleared in neolithic times and that the barren moors of the North, once forested were cleared and then farmed with sheep before Roman occupation. While the Brigantes did have sheep in their diet, the historical record of Anglo-Saxon Ley name places - ie clearing in woods along with the survival of wolves, wild boar, deer, and even a cave bear in Yorkshire does tend to suggest that forestation in Yorkshire was more extensive into Roman times and the Middle Ages than current thinking. If agriculure co-existed with forestation, perhaps the presence of agriculture in pollen samples does not exclude the survival of wooded landscapes. Evidence abunds for the survival of large numbers of Wolves in the North and the West :

Certain historians write that in 950, King Athelstan imposed an annual tribute of 300 wolf skins on Welsh king Hywel Dda,[4] while William of Malmesbury states that Athelstan requested gold and silver, and that it was his nephew Edgar the Peaceful who gave up that fine and instead demanded a tribute of wolf skins on King Constantine of Wales. Wolves at that time were especially numerous in the districts bordering Wales, which were heavily forested.[5]

This imposition was maintained until the Norman conquest of England.[4] At the time, several criminals, rather than being put to death, would be ordered to provide a certain number of wolf tongues annually.[6]

The monk Galfrid, whilst writing about the miracles of St. Cuthbert seven centuries earlier, observed that wolves were so numerous in Northumbria, that it was virtually impossible for even the richest flock-masters to protect their sheep, despite employing many men for the job. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that the month of January was known as “Wolf monath”, as this was the first full month of wolf hunting by the nobility. Officially, this hunting season would end on 25 March; thus it encompassed the cubbing season, when wolves were at their most vulnerable, and their fur was of greater quality.[1]In the eleventh year of Henry VI's reign (1433), a Sir Robert Plumpton held a bovate of land called “Wolf hunt land” in Nottingham, by service of winding a horn and chasing or frightening the wolves in Sherwood Forest. The wolf is generally thought to have become extinct in England during the reign of Henry VII (1485–1509), or at least very rare. By this time, wolves had become limited to the Lancashire forests of Blackburnshire and Bowland, the wilder parts of the Derbyshire Peak District, and the Yorkshire Wolds. Indeed, wolf bounties were still maintained in the East Riding until the early 19th century.[5]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolves_in_Great_Britain

In Europe wolves survive in many countries where there is significantly higher levels of forestation that Modern England where deforestation and wolf hunting made the wolf population extinct.

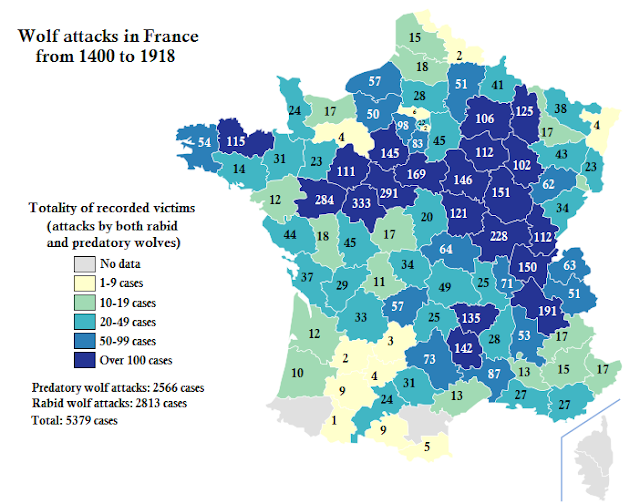

A map of historic wolf attacks in France shows one of the reasons Wolves were hunted in England.

You have no idea how long I've been looking for a reasonable map of these forests. Thank you so much!

ReplyDelete